company

type

role

team

-

OBJ | VISUALS

designer | researcher

-

2022 - 2024

Abstract

This project represents one of my long-term engagements with the visual and spatial traditions of Persian Miniature painting. My research initially centered on investigating how spatial perception in these paintings is constructed through geometry and unconventional use of viewing angles. A comparative study with Renaissance painting highlighted a critical divergence: whereas Renaissance works employ linear perspective and a vanishing horizon to organize space, Persian Miniatures offer a radically different approach — one where the entirety of a scene is revealed simultaneously, without subordination to a single focal point. This simultaneity, I argue, is not only a formal characteristic but a storytelling device, allowing multiple narratives and temporalities to unfold within a single visual field.

Through this project, I sought not merely to analyze these miniature paintings as historical artifacts but to actively engage with and reinterpret their spatial logic. A central discovery emerged: Persian Miniature compositions resist categorization within Western systems of spatial representation, such as linear perspective, isometric, or axonometric projection. Instead, they operate through what I term a “collage of perspectives” — a dynamic assemblage of multiple viewpoints that together create a uniquely fluid spatial experience. This concept has become a guiding principle in the experimental visual work that forms the core of this research.

The School of Athens 1511–1509, by Raphael

Yusuf and Zulaikha (Joseph chased by Potiphar›s wife) 1488, by Behzād

Methodology & Process

My approach to this project was deliberately experimental and interdisciplinary, combining methods of visual analysis, digital modeling, and creative reinterpretation.

I began by closely studying a range of Persian Miniature paintings, focusing on the construction of space, the arrangement of figures, and the implied movement of the viewer’s eye across the scene. Rather than treating these paintings as static images, I considered them as active spaces — environments that invite nonlinear navigation. Early on, I drew comparisons to Renaissance spatial strategies, identifying the absence of vanishing points and the flattening of hierarchical depth in the Persian works. These observations led to a working hypothesis: that Persian Miniature spaces are inherently non-perspectival and multi-positional.

To test and expand this hypothesis, I translated selected miniature scenes into 3D digital models. Using 3D software, I experimented with reconstructing these spaces, deliberately refraining from imposing Western perspectival logic. Instead, I allowed the multiple viewpoints present in the original paintings to inform the construction of layered, unfolded, and often contradictory spaces. This 3D modeling process was not intended to “correct” or “complete” the miniatures but to better understand their internal spatial rules through a hands-on, practice-based inquiry.

Building on the 3D experiments, I developed a series of drawings and images that further explored these spatial principles. In this phase, I employed artificial intelligence tools as a means of generative manipulation — not to automate the process, but to extend the possibilities of recombining and reconfiguring spatial elements according to the logic of collaged perspectives. AI was treated as an instrument of distortion and reassembly, echoing the pluralistic and layered vision of the miniatures themselves.

Throughout this process, a key insight emerged: in Persian Miniature painting, space is not singular, fixed, or universal. Instead, it is contingent, multifaceted, and narrative-driven. The “collage of perspectives” that I observed — and sought to recreate — challenges linear visuality and invites a more pluralistic understanding of spatial experience, both historically and in contemporary visual practice.

My Early 3d studies on Yusuf and Zulaikha (Joseph chased by Potiphar›s wife) 2022, by Saleh Hariri

My Early perspective studies on Yusuf and Zulaikha (Joseph chased by Potiphar›s wife) 2022, by Saleh Hariri

Collage of Points of View: Creative Application

Following my initial experimental phase of reconstructing Persian Miniature spaces through 3D modeling and AI-based manipulation, I moved toward a more deliberate creative exploration. In this stage, I sought not merely to analyze or reinterpret existing miniatures, but to generate entirely new compositions inspired by the spatial logic I had uncovered — what I termed a “collage of points of view.”

Rather than adhering to a single perspective system, I intentionally constructed scenes that combined multiple, sometimes conflicting, viewpoints within a single frame. Each element of the scene — architecture, figures, landscape — was oriented according to its own localized logic, reflecting how, in Persian Miniature, space is often fragmented yet harmoniously interconnected. This method allowed for a dynamic and layered spatial experience, where no single vanishing point or organizing axis dictates the viewer’s gaze.

To achieve this, I worked through both manual and digital techniques. I created hand-drawn studies where I mapped different perspectives onto a shared compositional field. In parallel, I used 3D software to fragment and reassemble modeled environments, treating each part almost like a modular unit governed by its own spatial rules. AI tools were again employed to suggest unexpected juxtapositions and deformations, helping to break the residual habits of singular viewpoint thinking.

The final images are thus not reconstructions of historical works but original compositions that embody a similar multiplicity of vision. By consciously embracing the tension between different perspectives, I aimed to create immersive, non-linear spatial narratives — spaces that resist quick consumption and instead invite the viewer to navigate multiple vantage points simultaneously, much like in traditional Persian Miniature storytelling.

This phase of the project marked a shift from analysis to synthesis, allowing me to engage more deeply with the poetics of space and the possibilities of contemporary reinterpretation of historical visual strategies.

Grid as Analytical Tool

In a subsequent phase of my research, I introduced the grid—a hallmark of modernist abstraction—as a methodological instrument to dissect and reinterpret the complex spatial configurations inherent in Persian Miniature paintings. Historically, the grid has served as a pivotal framework in modern art, symbolizing a move towards abstraction and a departure from traditional perspective. Art historian Rosalind Krauss notably described the grid as emblematic of modernity, asserting that it “functions to declare the modernity of modern art” by emphasizing the flatness and autonomy of the pictorial plane.

By overlaying grid structures onto the intricate compositions of Persian Miniatures, I aimed to analytically unravel their spatial logic. This process involved mapping the multiple, often conflicting, viewpoints present in the miniatures onto a unified grid system. The exercise revealed that, unlike the singular perspective of Renaissance art, Persian Miniatures employ a “collage of perspectives,” where various spatial narratives coexist within a single frame. The grid, in this context, became a tool to visualize and understand these overlapping spatial constructs.

Furthermore, this analytical approach allowed for a deeper exploration of the geometric principles underlying the miniatures. The grid facilitated the identification of recurring patterns, symmetries, and spatial hierarchies that might otherwise remain obscured. By deconstructing the miniature space through the lens of the grid, I could engage with the artwork’s geometry not just aesthetically, but also intellectually, bridging traditional art forms with contemporary analytical methods.

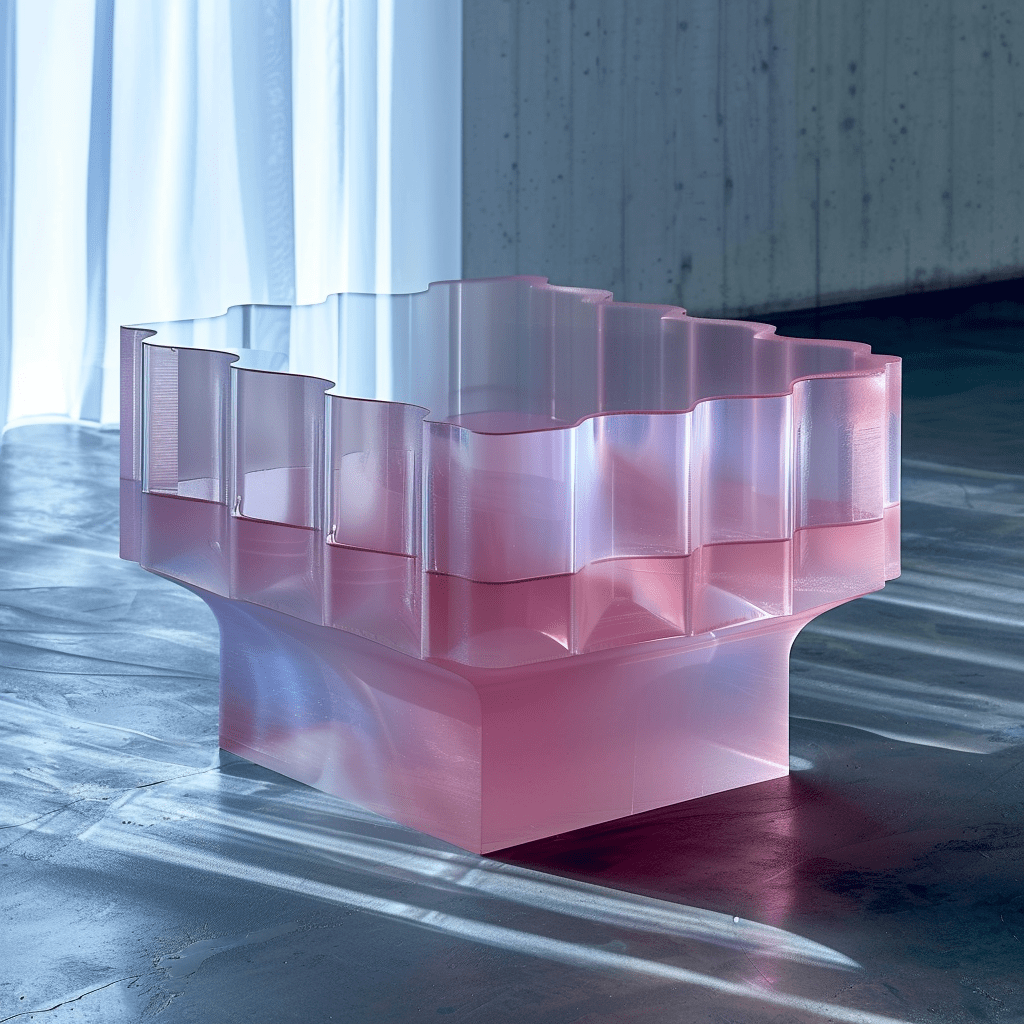

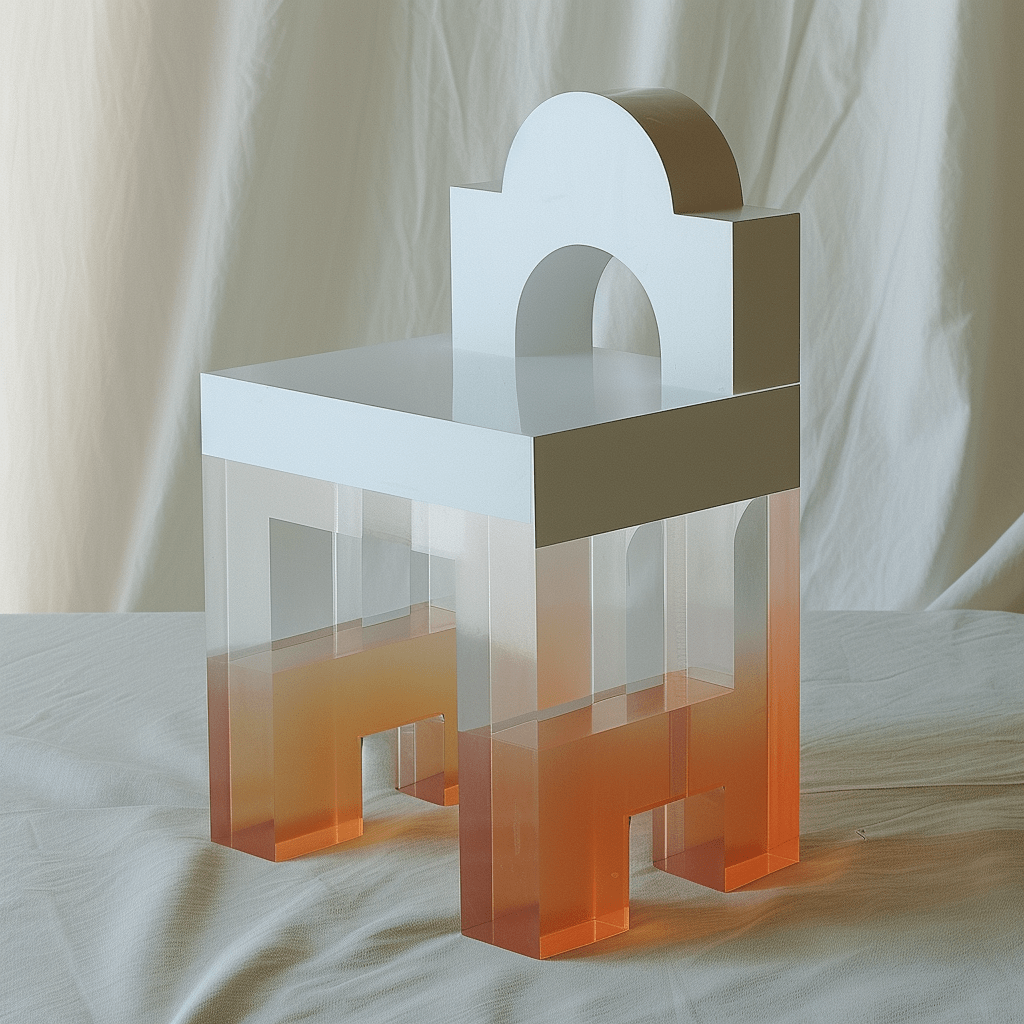

To Object

Building upon the earlier phases of spatial analysis and reconstruction, the next stage of my project focused on translating two-dimensional spatial principles into three-dimensional objects. This progression — from analyzing flat compositions to designing volumetric forms — was a natural extension of the insights I had gained from studying the “collage of perspectives” and the geometric structure underlying Persian Miniature paintings.

Using the spatial rules and compositional strategies I had discovered during the drawing experiments, I began to design new objects that could exist within the miniature-inspired environments I was creating. Rather than inserting random or purely decorative elements, each object was conceived with careful attention to the internal logic of the scene: its scale relative to other elements, its orientation according to multiple points of view, and its relationship to the fractured, layered spatial system.

Initially, these objects were sketched directly into the two-dimensional drawings, serving as tests of how new forms could inhabit and expand the miniature space. Following these sketches, I extracted the designed objects into three-dimensional digital space, modeling them in 3D software. In doing so, I treated the objects not simply as static sculptures, but as dynamic spatial nodes that further complicated and enriched the collage of viewpoints within each scene.

This phase allowed me to more fully explore how traditional concepts of space and form could be challenged and reimagined through a contemporary lens. It also shifted the project from a focus purely on spatial analysis toward the active construction of a hybrid visual language — one that bridges miniature painting, modernist abstraction, and experimental digital fabrication.

By designing and modeling these objects, I was not only building elements to populate a scene; I was testing how far the logic of the miniature could be stretched into physicality, how multiple perspectives could be embodied in single, tangible forms. This opened new possibilities for future stages of the project, including potential installations, sculptures, or immersive virtual environments based on the same core principles.

Framings of the Persian Miniature

During the course of my research on Persian Miniature painting, the concept of framing emerged as a crucial structural and symbolic element within the visual language of the tradition. Framing in miniatures is far more than a decorative boundary; it operates as an active spatial device, organizing narrative, guiding perception, and often serving to mediate the relationship between multiple spatial realities contained within a single composition.

In this phase of my project, I deliberately concentrated on the use and reinterpretation of frames, drawing direct inspiration from historical examples of Persian miniature art. One particularly striking case is The Funeral of the Elderly Attar of Nishapur, painted by Behzād in 1486. This work captures the aftermath of Attar’s death at the hands of a Mongol invader and is notable not only for its emotive storytelling but also for its distinctive use of framing. The scene is enclosed within ornate, layered borders that do not merely separate the image from the external world but actively shape the viewer’s experience of the narrative space. The frame operates almost like a threshold — a portal through which the viewer enters a multi-layered temporal and spatial field.

Inspired by such examples, I approached framing in my own compositions not as a passive decorative element but as an integral part of the spatial construction. In my collection, frames are designed to interact dynamically with the internal logic of the scenes. Sometimes they serve to fragment the space, reinforcing the “collage of perspectives” by visually splitting different zones within the same image. At other times, they act as transitional devices, subtly suggesting shifts between narrative episodes or different scales of spatial experience.

At the next stage of object design, I extended this focus by treating borders and framing as essential aesthetic elements in their own right. Rather than thinking of frames only as peripheral devices, I began to design objects where the frame itself became an active spatial form — sometimes functioning as an enclosure, a window, or a boundary that shaped both the viewer’s gaze and the object’s interaction with its surroundings. This shift allowed me to explore how the aesthetic principles of framing could be materialized into three-dimensional space, blurring the line between image, object, and environment.

Through this deepened exploration of framing, I aimed to continue the miniature’s complex interplay between containment and expansion, intimacy and openness, extending traditional visual strategies into contemporary spatial experiments.

Non-Functional Objects

Throughout my research and creative experimentation, I became increasingly interested in the role of objects that exist beyond pure functionality — objects that carry cultural meanings, stories, and beliefs embedded within their forms. I believe that by examining non-functional objects within a given place or society, one can uncover deep insights about its values, rituals, and collective imagination. These objects often serve as vessels of intangible cultural heritage, rooted not in their practical use, but in symbolic and narrative dimensions.

Recognizing this, I decided to dedicate a phase of my project to exploring and designing such objects. Drawing inspiration from the Persian Miniature tradition — where many depicted objects, from architectural elements to symbolic artifacts, exist as carriers of layered meanings — I sought to reimagine this idea in a contemporary context.

In this stage, I focused on designing objects that were intentionally freed from strict utilitarian purposes. Instead, their existence within the space was justified by the stories they suggested, the beliefs they embodied, and the emotions they evoked. Each object was conceived as a fragment of a larger, often untold narrative — a physical marker of memory, mythology, or a reinterpreted cultural symbol.