2024

Table of Contents

Introduction

Video games, much like cinema, create rich, immersive worlds that extend far beyond what we see on the screen. While on-screen spaces provide immediate action and interaction, off-screen spaces—the hidden, implied, or suggested areas just out of view—are just as important in shaping the player’s experience. These unseen spaces add depth, making game worlds feel larger, more connected, and more alive. Whether it’s the suggestion of an expansive city beyond a level’s boundary, the footsteps of an unseen enemy, or a hidden room waiting to be discovered, off-screen spaces fuel curiosity, imagination, and engagement.

Mark J. P. Wolf, in his work Inventing Space: The Use of On-Screen and Off-Screen Space in Video Games, explores how video games build these spaces and how they compare to film. He explains that while movies imply off-screen areas through framing and sound, video games go a step further by letting players interact with and sometimes even uncover these hidden spaces. From early arcade games with static screens to modern 3D worlds, Wolf maps out how video games have used off-screen space to create a sense of place, mystery, and anticipation.

This paper builds on Wolf’s ideas but also pushes them further by looking at how modern games challenge traditional concepts of off-screen space. Today’s open-world games, virtual reality experiences, and procedurally generated environments blur the lines between what’s seen and unseen in ways that weren’t possible when Wolf first wrote about these ideas. While his taxonomy is still useful, it may not fully capture how games today handle space and immersion. By critically examining his framework in light of modern gaming, this paper aims to highlight the evolution of off-screen spaces, uncover gaps in Wolf’s analysis, and explore what these hidden spaces mean for storytelling, player immersion, and game design in the present and future.

Off-Screen Spaces in Wolf's Perspective

Mark J. P. Wolf’s discussion of off-screen space in video games is deeply rooted in the idea that video games present a unique spatial structure compared to cinema. He notes that “off-screen space in a video game does not have a pro-filmic referent the way a filmed space often does” (Wolf, M.J.P. (1997). Inventing space: Toward a taxonomy of on- and off-screen space in video games. Film Quarterly, 51(1), p.12). This means that in film, off-screen space is implied by the camera’s limitations, but in video games, it must be actively programmed and structured. Unlike film, where the camera captures an existing reality, video games create their worlds entirely through programming. Thus, the conceptualization of space is not bound to the physical constraints of a film set or real-world physics.

One of the most significant aspects of off-screen space in video games is the player’s ability to explore it. Wolf explains that in many video games, “off-screen space can often be investigated and explored” (Wolf, M.J.P. (1997). Inventing space: Toward a taxonomy of on- and off-screen space in video games. Film Quarterly, 51(1), p. 12), a feature that differentiates games from film. In games like Adventure (1978), Doom (1993), and Dark Forces (1994), the unseen areas of the game world are an integral part of gameplay. Players must navigate through these spaces, often experiencing them only when they choose to move their character or camera into them.

Adventure (1978)

Doom (1993)

Dark Forces (1994)

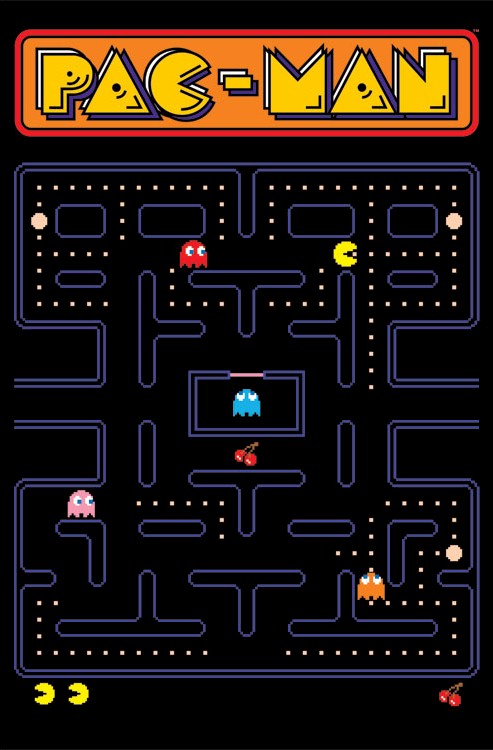

Another fundamental distinction Wolf makes is that off-screen space in games is not a passive element—it is part of the interactivity that defines the medium. In early games like Pac-Man (1980), for example, tunnels that allow the character to disappear from one side of the screen and reappear on the other create an implied off-screen space. However, because the player controls when and how to navigate these spaces, the experience of off-screen space is active rather than passive. This is unlike film, where off-screen space is determined by the director’s choices and the camera’s framing.

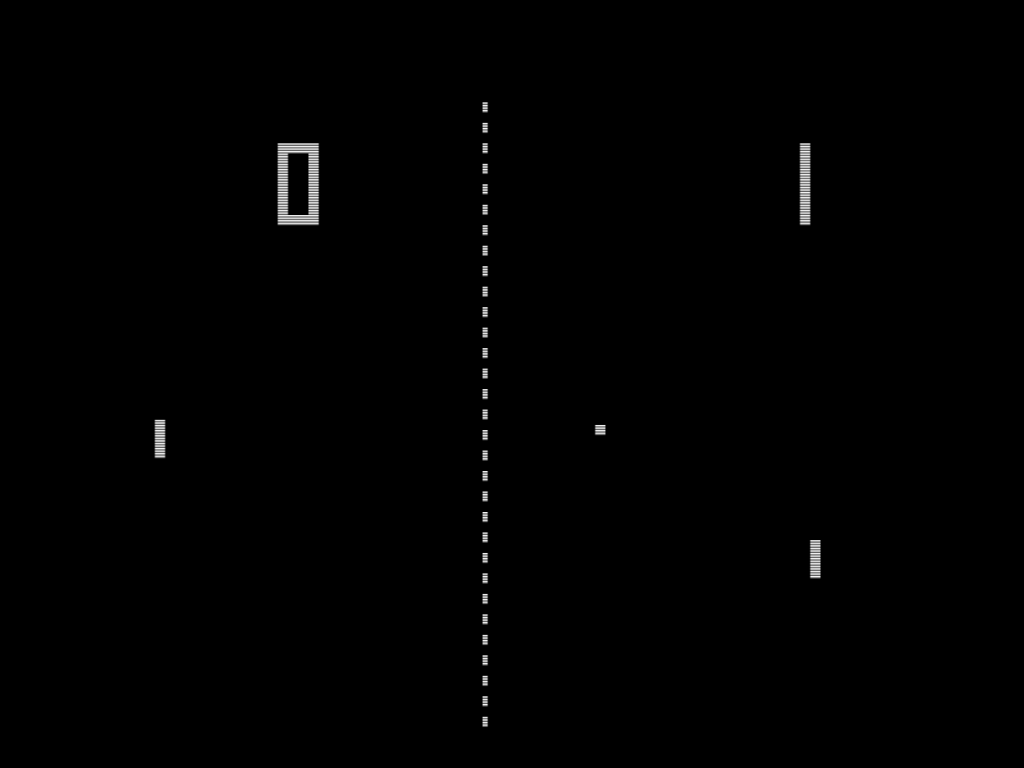

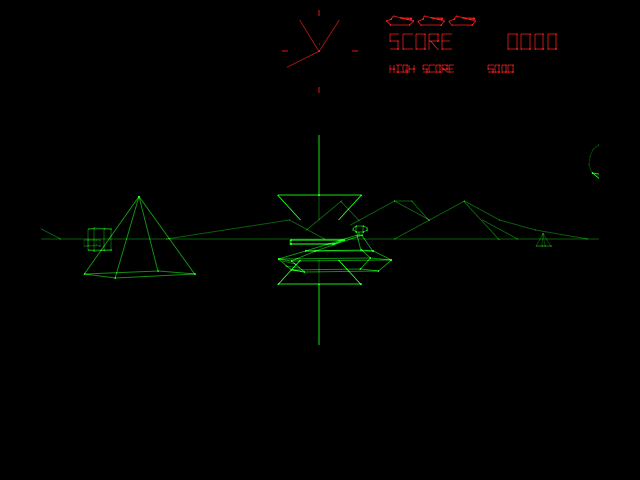

Wolf also discusses how video games, particularly with technological advancements, have experimented with different spatial structures. Early games had limited off-screen spaces, with everything happening within the boundaries of a single screen (Pong, 1972). However, as game worlds expanded, scrolling screens (Defender, 1982), adjacent screens (Adventure, 1978), and later fully interactive three-dimensional environments (Doom, Quake, 1996) allowed players to experience off-screen spaces dynamically.

Furthermore, Wolf emphasizes that off-screen space in video games is often mapped for player reference. Many games include radar or mini-maps that provide a conceptual view of off-screen areas. This is particularly notable in games like Battlezone (1980), which used a radar screen to indicate enemy positions outside the player’s immediate view, or Myst (1993), where a physical in-game map guided exploration. Unlike film, where off-screen space is inferred and left to audience imagination, video games provide tangible, interactive tools to engage with unseen areas.

Pac-Man (1980)

Pong (1972)

Defender (1982)

Battlezone (1980)

Major Differences Between Cinema and Video Games in Wolf’s Work

Wolf makes several distinctions between cinema and video games, particularly in how they handle spatial representation. He argues that “video games, unlike film, are interactive media, allowing players to control aspects of the experience, including movement and navigation through space” (p.14). This fundamental difference affects how space, particularly off-screen space, is utilized in both mediums.

- Fixed vs. Navigable Space

In film, spatial representation is constrained by the director’s choices. The camera determines what is seen and unseen, and the audience passively absorbs the given visual information. In contrast, video games grant players agency in exploring space. In a film like Casablanca (1942), Rick’s Café is presented through carefully framed shots, whereas in a game like Myst, the player actively moves through environments, uncovering new locations. - Editing vs. Continuous Space

Another major difference Wolf discusses is how space transitions occur in film versus video games. Cinema relies on editing techniques—cuts, dissolves, panning, etc.—to move between locations. In video games, transitions between spaces can be abrupt (cutting from one screen to another in Adventure), smooth (scrolling in Super Mario Bros., 1985), or even seamless (continuous first-person movement in Doom). Wolf notes that while early games adopted a filmic approach with “adjacent spaces displayed one at a time” (Wolf, M.J.P. (1997). Inventing space: Toward a taxonomy of on- and off-screen space in video games. Film Quarterly, 51(1), p.16), later games created fully explorable, immersive worlds. - Viewer vs. Player Engagement

In film, the audience is a spectator, whereas in video games, the player is an active participant. Wolf explains that “knowledge of the video game’s space is often crucial to a good performance” (Wolf, M.J.P. (1997). Inventing space: Toward a taxonomy of on- and off-screen space in video games. Film Quarterly, 51(1), p.17). A filmgoer does not need to memorize a set’s layout to understand a story, but a gamer must remember the layout of a labyrinth in Quake to progress. This difference in spatial engagement fundamentally separates the mediums. - Off-Screen Space as a Gameplay Mechanic

In film, off-screen space is often used for narrative and suspense. A character may react to something off-screen, or an unseen element may build tension. In contrast, in video games, off-screen space is an interactive element. Wolf points out that in Spy vs. Spy (1984), players must watch each other’s screens to anticipate movements, making off-screen space a tactical part of gameplay. Similarly, in Battlezone, sounds indicate enemy movement in off-screen areas, forcing the player to react accordingly. - The Evolution Toward Three-Dimensionality

Wolf also discusses how video games have moved towards more cinematic spatial representations. With 3D games like Doom, Descent, and Quake, games have adopted filmic techniques such as depth, perspective shifts, and environmental storytelling. However, unlike film, these spaces are not just visual constructs; they are explorable worlds. This shift means that while video games borrow cinematic techniques, they extend them through interactivity. - Technological Influence on Space

Finally, Wolf emphasizes that video game spatial representation is deeply influenced by technological advancements. Early games had minimal off-screen space due to hardware limitations, but modern games with advanced rendering techniques allow vast, detailed worlds. This has resulted in a convergence, where “the gap between games and film continues to close” (Wolf, M.J.P. (1997). Inventing space: Toward a taxonomy of on- and off-screen space in video games. Film Quarterly, 51(1), p.13). However, the key difference remains interactivity—film will always be a guided experience, while video games rely on player agency.

Critical approach to Wolf’s taxonomy of space in video games

Mark J. P. Wolf’s taxonomy of space in video games provides an essential framework for understanding the spatial structures that shape gameplay and player perception. His categorization of on-screen and off-screen space was particularly significant at the time of its publication, as it offered a structured way to analyze the spatial logic of early and mid-1990s video games. However, the rapid evolution of gaming technology, design philosophies, and player expectations has outpaced his framework, rendering aspects of his taxonomy inadequate for analyzing modern video game spaces. The increasing complexity of game worlds, interactivity, and real-time adaptability in modern games exposes several key shortcomings in Wolf’s taxonomy.

Overemphasis on the Static Nature of Off-Screen Space

Wolf’s taxonomy of space largely treats off-screen space as an extension of the visible world, often implying a static relationship between the two. His framework categorizes off-screen space into clear segments based on the ways players perceive and interact with unseen areas. However, modern video games frequently disrupt this static conceptualization by making off-screen space an active and evolving element of gameplay. For instance, in open-world games like The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild (2017) or Red Dead Redemption 2 (2018), off-screen space is not merely an extension of the on-screen world but is dynamically generated, filled with emergent gameplay elements, and constantly shifting based on player actions. Wolf’s rigid classifications fail to accommodate the fluidity of these spaces.

Additionally, Wolf’s model often assumes a clear distinction between on-screen and off-screen areas, whereas modern games increasingly blur these boundaries. Techniques such as dynamic camera control, real-time rendering adjustments, and diegetic UI elements make it difficult to pinpoint where the player’s perceptual boundary of off-screen space truly begins. For example, in games like God of War (2018), the single-shot camera design ensures that the player never perceives a traditional off-screen space in the same way that Wolf’s model describes.

The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild (2017)

God of War (2018)

Red Dead Redemption 2 (2018)

Limited Integration of Temporality

Wolf’s taxonomy does not explicitly address how off-screen space changes over time, a crucial oversight when considering modern games that utilize evolving environments and dynamic spatial configurations. Many contemporary games feature spaces that are not permanently fixed in accessibility or visibility. Instead, off-screen areas can transform based on narrative progression, player choices, or procedural generation.

For example, in Dark Souls (2011) and its successors, spaces that are initially off-limits due to locked doors, barriers, or impassable obstacles can later become available, fundamentally altering the game’s spatial logic. Similarly, in procedurally generated games like Minecraft or No Man’s Sky, off-screen space is not pre-defined but continuously generated as the player moves through the world. The concept of off-screen space in such games is tied directly to temporality, with new areas emerging unpredictably rather than conforming to Wolf’s static taxonomy.

Dark Souls (2011)

Insufficient Attention to Peripheral Spaces

Peripheral spaces, or areas that exist at the fringes of the player’s field of vision but remain inaccessible, are not sufficiently explored in Wolf’s taxonomy. While he acknowledges off-screen space as an area beyond the immediate visual scope, his framework does not fully capture the role of partially visible, yet unreachable, game spaces in modern game design. Peripheral spaces serve a crucial function in immersion and world-building, creating the illusion of a vast and continuous game world.

In games like The Witcher 3: Wild Hunt (2015), vast landscapes stretch beyond the player’s immediate control, suggesting continuity while remaining inaccessible. Similarly, Half-Life 2 (2004) makes extensive use of distant cityscapes and unreachable structures to reinforce its narrative and environmental storytelling. These peripheral spaces influence how players perceive the game world’s scale and depth, yet they do not fit neatly into Wolf’s rigid on-screen/off-screen binary.

Moreover, modern games frequently use peripheral spaces to create tension and engagement. In horror games like Resident Evil Village (2021), unseen threats loom just outside the player’s direct field of view, leveraging sound design and lighting to suggest danger in these peripheral areas. These design elements actively manipulate the player’s perception of off-screen space, which is a crucial aspect that Wolf’s model does not account for.

The Witcher 3: Wild Hunt (2015)

Resident Evil Village (2021)

The Role of the Player in Navigating Off-Screen Space

Wolf’s taxonomy does not adequately address the active role that players have in engaging with and shaping off-screen space. His framework largely assumes that off-screen areas exist independently of player agency. However, modern games increasingly empower players to influence and interact with these spaces in meaningful ways.

For instance, many contemporary games feature mechanics that allow players to directly manipulate off-screen space through actions such as scouting, marking, or revealing unexplored areas. In Horizon Zero Dawn (2017), players can use a scanning ability to highlight enemies and environmental elements beyond their immediate field of vision, effectively integrating off-screen space into their strategic planning. Similarly, tactical games like XCOM 2 (2016) make use of a fog-of-war system, where off-screen space is not merely hidden but is an essential part of the player’s decision-making process.

Additionally, modern virtual reality (VR) games further challenge the notion of a fixed off-screen space. In VR experiences like Half-Life: Alyx (2020), players can physically turn their heads and reposition their perspective, effectively redefining what constitutes on-screen and off-screen space at any given moment. This real-time interaction with off-screen elements is fundamentally different from the static conceptualization found in Wolf’s taxonomy.

Half-Life: Alyx (2020)

Horizon Zero Dawn (2017)

A new alternative to the taxonomy of off-screen spaces in video games

Off-screen space in video games plays a crucial role in shaping player perception, guiding exploration, and enhancing world-building. While Mark J. P. Wolf’s original taxonomy laid the groundwork for understanding the function of on- and off-screen spaces, modern video games have evolved to make off-screen spaces more interactive, immersive, and dynamic. In order to refine this framework, we can categorize off-screen spaces into three primary types: Implied but Inaccessible Space, Temporarily Inaccessible Space, and Peripheral Space. Each of these contributes to the player’s understanding of the game world, whether by hinting at unseen areas, restricting access until progression allows it, or providing a partially visible extension of the playable environment.

1- Implied but Inaccessible Space, refers to areas that are suggested through visual, auditory, or narrative cues but are never actually accessible to the player. These spaces are an essential part of world-building, as they create the illusion of a larger environment that extends beyond the playable area. They may take the form of locked doors, distant landmarks, or background activity, all of which provide a sense of depth and immersion. For example, in Resident Evil, the player frequently encounters locked doors that contribute to the game’s atmosphere, even if they never open. Similarly, in open-world games like The Elder Scrolls V: Skyrim, vast mountains or distant cities remain visible but forever unreachable, reinforcing the idea that the game world extends far beyond what is explorable. Implied spaces can also be conveyed through sound, such as hearing NPCs talk behind walls or distant battles taking place beyond the player’s reach. These auditory cues make the game world feel alive and persistent, even if the player never directly interacts with those elements. By incorporating such spaces, game designers can create a sense of mystery and intrigue, encouraging players to imagine the unseen portions of the world. This category is particularly effective in horror or narrative-driven games, where suggesting rather than showing can build tension and enhance storytelling. Ultimately, implied but inaccessible spaces are designed to expand the perceived scale of a game without requiring additional resources, serving as an economical yet effective method of creating a believable world.

2-Temporarily Inaccessible Space, includes areas that the player cannot initially access but can reach later through game progression. Unlike implied spaces, which remain permanently off-limits, these spaces tease the player with the promise of future exploration. They are often tied to game mechanics, such as unlocking new abilities, acquiring key items, or advancing through the storyline. A prime example of this is found in Metroidvania games like Hollow Knight, where players encounter barriers that can only be overcome after obtaining specific upgrades, such as the double jump or wall climb. Similarly, in RPGs like The Witcher 3, certain regions are inaccessible until the player advances the main quest, ensuring that the world unfolds in a structured and controlled manner. Temporarily inaccessible spaces are particularly effective at encouraging backtracking and fostering a sense of accomplishment when the player finally gains access to them. In some cases, these spaces evolve over time, such as a collapsed bridge being rebuilt or a blocked cave becoming accessible after a key event. This category also adds an element of anticipation, as players may notice intriguing locations early in the game and remain eager to explore them later. The deliberate restriction of access ensures that players follow a well-paced progression rather than rushing through the game. Moreover, this approach increases replayability, as players who revisit earlier areas often discover new secrets, optional content, or upgraded challenges that were previously unavailable. By strategically implementing temporarily inaccessible spaces, game designers create a structured experience that balances curiosity, challenge, and reward.

3-Peripheral Space consists of areas that are partially visible or interactive but never fully explorable. These spaces function as extensions of the game world, serving as natural boundaries that prevent players from feeling confined while still maintaining spatial coherence. They can include distant landscapes, unreachable buildings, or NPCs and wildlife that exist on the edge of the playable area. For example, in Assassin’s Creed, players can often see vast cities, towering mountains, or ships sailing in the distance, reinforcing the illusion of a sprawling historical world. Similarly, in games like Dark Souls, mysterious figures can be glimpsed on distant cliffs or in unreachable locations, creating a sense of scale and interconnectedness. Some peripheral spaces allow limited interaction, such as the ability to fire into distant battles or trigger minor environmental reactions, even if full access is restricted. This is often seen in games where background elements respond to the player’s presence, such as birds flying away in The Last of Us or far-off enemy patrols shifting their behavior based on the player’s actions. Peripheral spaces also play a psychological role, subtly directing the player’s attention toward more important gameplay areas while maintaining a sense of freedom. Unlike implied spaces, which are entirely off-limits, and temporarily inaccessible spaces, which eventually open up, peripheral spaces are a permanent yet visually integrated part of the game world. They function as a visual buffer, preventing the stark realization of hard boundaries while preserving immersion.

Techniques for Representing Off-Screen Space in Modern Video Games

Game designers use a variety of clever techniques to make off-screen spaces feel alive and meaningful, enhancing immersion and gameplay depth. By looking at how games have evolved over time, we can see how these techniques shape the player experience.

1. Visual Cues and Off-Screen Space

Games use visual tricks to make the world feel bigger than what’s visible on the screen. Whether through detailed backgrounds, disappearing objects, or layered movement, these techniques help players sense that there is more to the world than what they immediately see.

Distant landscapes and backgrounds in open-world games like Grand Theft Auto V (2013) or The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild (2017) give the impression of a vast world waiting to be explored. These scenic elements help players feel grounded in a larger, living environment.

Objects or enemies briefly appearing before retreating off-screen create curiosity and anticipation. In platformers and horror games, seeing only part of an enemy before it disappears makes players aware of lurking dangers.

Parallax scrolling, where background layers move at different speeds compared to the foreground, adds depth. Games like Hollow Knight (2017) use this effect to make environments feel richer and more dynamic.

2. Auditory Cues: Hearing Beyond the Screen

Sound plays a huge role in making off-screen spaces feel alive. Audio cues help players sense movement, danger, or hidden details beyond the visible area, enhancing immersion and guiding player decisions.

Footsteps, distant conversations, or environmental sounds give players clues about what’s happening beyond their line of sight. Horror games like Resident Evil (1996) and Silent Hill (1999) use unsettling noises to build suspense and hint at hidden threats.

Directional sound design helps players track enemies or important events. In first-person shooters like Doom Eternal (2020), the placement of gunfire and monster growls gives players an idea of where danger is coming from, even before they see it.

3. Gameplay and Interactions with Off-Screen Spaces

Off-screen spaces aren’t just there for atmosphere—they’re often tied directly to gameplay, shaping how players explore and interact with the world. Whether through hidden areas, fog-of-war mechanics, or AI behaviors, these spaces influence player strategy and engagement.

Hidden areas and secret paths in Metroidvania games like Hollow Knight (2017) and Castlevania: Symphony of the Night (1997) reward exploration. These areas remain off-screen until players uncover them, making discovery part of the fun.

Fog of war mechanics in strategy games like Civilization VI (2016) or Starcraft (1998) obscure unexplored parts of the map, revealing them as players move through the world. This mirrors mapped spaces, where the game acknowledges unseen areas but only reveals them when necessary.

AI behaviors that continue off-screen make game worlds feel more alive. In The Last of Us (2013) and Red Dead Redemption 2 (2018), NPCs go about their routines even when they’re out of sight, reinforcing the illusion of a dynamic world.

4. Seamless Transitions and Camera Tricks

How a game moves between on-screen and off-screen space can make a big difference in how natural and immersive it feels. Clever camera work and transitions help create a sense of continuity and fluid movement between spaces.

Camera tracking and framing subtly guide the player’s focus. God of War (2018) uses a seamless, one-shot camera to follow Kratos, keeping players engaged with the world without any noticeable cuts.

Loading screen transitions used in older games, like Resident Evil (1996) with its door animations, cleverly mask loading times while making the world feel connected.

Split-screen or picture-in-picture views, as seen in Spy vs. Spy (1984) or multiplayer shooters, let players monitor off-screen spaces in real-time. This approach, similar to showing multiple nonadjacent spaces at once, is especially useful in competitive game

Grand Theft Auto V (2013)

Spy vs. Spy (1984)

Doom Eternal (2020)

Conclusion

Off-screen spaces in video games serve as powerful tools for world-building, storytelling, and player engagement. As Mark J. P. Wolf illustrates, these spaces shape a game’s sense of place, extending the player’s perception beyond the visible frame. While his taxonomy effectively categorizes how games have traditionally used off-screen space, the evolution of gaming technology—especially in open-world, VR, and procedurally generated games—demands a broader perspective. Today, off-screen spaces are more dynamic, not only implied or suggested but often interactable in ways that challenge the boundaries between seen and unseen.

By examining Wolf’s framework in the context of modern gaming, this paper has highlighted the growing complexity of off-screen spaces and their role in immersion. While his foundational ideas remain relevant, contemporary games push the limits of spatial representation, creating experiences where what lies beyond the screen is just as vital as what is directly visible. As game worlds continue to expand and evolve, so too must our understanding of how these hidden spaces contribute to player curiosity, engagement, and narrative depth. Future research and analysis should explore how emerging technologies further redefine off-screen space, ensuring that Wolf’s insights continue to evolve alongside the medium itself.

Bibliography

- Wolf, M.J.P. (1997) Inventing space: Toward a taxonomy of on- and off-screen space in video games. Film Quarterly, 51(1)